Comparing three or more means¶

[1]:

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import math

import scipy.stats

import statsmodels.stats.multicomp

age_shf = pd.read_pickle("../data/processed/age_shf")

age_ebn = pd.read_pickle("../data/processed/age_ebn")

age_oxf = pd.read_pickle("../data/processed/age_oxf")

# we want just a sample; a population is more likely to be statistically significant!

age_shf = age_shf.sample(n = 1000, replace = True, random_state = 42)

age_ebn = age_ebn.sample(n = 1000, replace = True, random_state = 42)

age_oxf = age_oxf.sample(n = 1000, replace = True, random_state = 42)

In the previous section we compared the means of two different groups to see if they were statistically significantly different. Specifically we tested to see if the mean age of residents of Eastbourne is greater than the mean age of residents of Sheffield, and it was. This suggests that, overall, the population of Eastbourne is older than the population of Sheffield, and so there might be some truth to the caricature that Eastbourne is a popular retirement destination.

But what if we want to compare the means of more than two groups? Could we perform multiple \(t\)–tests? Well, no. It has been argued that the process of performing multiple \(t\)–tests is laborious because you need to perform one for each pair of means. These days, with the automation provided by computers, we no longer need to do the tests manually so this is no longer relevant; performing multiple \(t\)–tests in a loop is now a trivial task with R or Python.

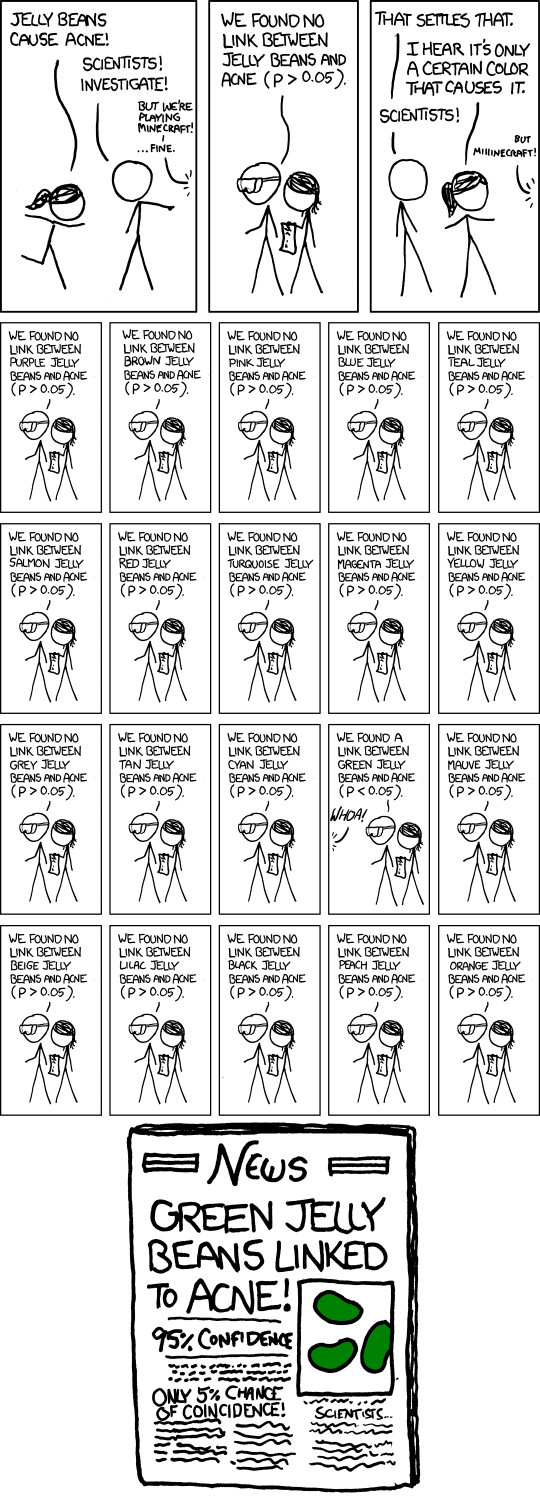

But, there’s a more important reason we shouldn’t perform multiple \(t\)–tests, even though we can. By performing multiple \(t\)–tests we increase the risk of making a Type I error. Remember we can never prove things with statistics, only calculate how likely something is to happen by chance alone.

By convention we use a threshold of 0.05, or less than a 5% chance that the results we observe are by chance. But at 5% there’s a 1 in 20 chance we commit a Type I error. So if we performed 20 pairs of \(t\)–tests we would be almost guaranteed to make at least one Type I error! XKCD, as always, neatly sums this up.

So instead of making multiple \(t\)–tests we perform an analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Example¶

For this example I use the ages of a sample of 1,000 people from Sheffield and Eastbourne as before, but to compare an additional mean I include a sample of 1,000 people from Oxford. Oxford is one of the youngest populations overall for any city in the UK, perhaps because of the student population, so this test will see if there is a difference between the ages of Oxford, Sheffield, and Eastbourne. Our null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) is therefore that there is no statistically significant difference between the mean ages of residents in Oxford, Sheffield, and Eastbourne.

Assumptions¶

The assumptions of ANOVA are, not surprisingly, very similar to those of a \(t\)–test:

- Measurements/observations are independent of each other (i.e. from different people)

- Measurements are on a continuous scale

- If the sample size is small the variables should have a normal distribution.

For our example the observations are independent (the ages of people in Sheffield do not affect the ages of people in Eastbourne or Oxford). Age is a continuous measure (even though it’s measured here on a discrete scale we can treat it as continuous). We have sample sizes of 1,000 per group so do not need to check for normality, but if we did we would plot a series of QQ plots as we did for \(t\)–tests.

Equality of variance¶

As with the \(t\)–test it is ideal if the variances of the three (or more) groups are equal, so we are looking for equality of variance. However, as a rule of thumb ANOVA is robust to differences in variance of up to 4x. That is, if the largest variance is no larger than 4x the smallest variance the ANOVA is still reliable.

First, let’s try a Levene test for equality of variance as we might not even need to worry about this:

[2]:

scipy.stats.levene(

age_oxf.C_AGE_NAME, age_shf.C_AGE_NAME, age_ebn.C_AGE_NAME

)

[2]:

LeveneResult(statistic=18.98095012875844, pvalue=6.43352435595419e-09)

Here the Levene statistic is statistically significant (\(p << 0.01\)) so we must reject the null that there is no difference between the variances, and assume that the variances are not equal. So is the largest variance less than 4x the smallest variance?

[3]:

max_var = max(age_shf.C_AGE_NAME.var(), age_ebn.C_AGE_NAME.var(), age_oxf.C_AGE_NAME.var())

min_var = min(age_shf.C_AGE_NAME.var(), age_ebn.C_AGE_NAME.var(), age_oxf.C_AGE_NAME.var())

print(max_var / min_var)

1.3360587582810752

The maximum variance is therefore less than twice as large as the minimum variance, so our rule of thumb holds for this data set and we can interpret the ANOVA as reliable.

ANOVA¶

[4]:

scipy.stats.f_oneway(

age_shf, age_ebn, age_oxf

)

[4]:

F_onewayResult(statistic=array([27.76084434]), pvalue=array([1.13223062e-12]))

The ANOVA result is statistically significant (\(p << 0.01\)) so there is a statistically significant difference between the mean ages of people in Sheffield, Eastbourne, and Oxford overall. Now let’s run some post–hoc tests to see which group(s) actually differ. First we should transform the data into ‘long’ form, so one row per obvservation. So that we know which observation is from which city I add a ‘city’ variable:

[5]:

age_shf = age_shf.assign(city = "Sheffield")

age_ebn = age_ebn.assign(city = "Eastbourne")

age_oxf = age_oxf.assign(city = "Oxford")

ages = age_shf.append(age_ebn)

ages = ages.append(age_oxf)

Now the post–hoc tests:

[6]:

posthoc = statsmodels.stats.multicomp.MultiComparison(

ages.C_AGE_NAME, ages.city

)

posthoc = posthoc.tukeyhsd()

print(posthoc)

Multiple Comparison of Means - Tukey HSD,FWER=0.05

====================================================

group1 group2 meandiff lower upper reject

----------------------------------------------------

Eastbourne Oxford -7.542 -9.9761 -5.1079 True

Eastbourne Sheffield -5.257 -7.6911 -2.8229 True

Oxford Sheffield 2.285 -0.1491 4.7191 False

----------------------------------------------------

The post–hoc tests suggest that there is a difference in ages between people in Oxford and Eastbourne, and Sheffield and Eastbourne, but not between Oxford and Sheffield. This would indicate that people in Eastbourne are older, on average, than people in Oxford or in Sheffield, but that people in Oxford are not younger than people in Sheffield overall.